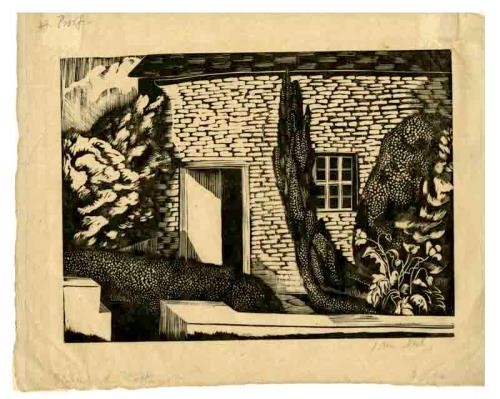

Wood engravings are often small, sometimes very small. This medium-size wood engraving (12.6 x 17.2cm) is an artist’s proof signed by John Nash, who has scribbled the title ‘Gloucestershire Cottage below the print and jotted ‘2 gns’ in the bottom right-hand corner. Here is The Wilson’s succinct catalogue description:

Print (wood engraving) entitled ‘Gloucestershire Cottage’, c.1920, by John Nash. 20th century, British School. View of end of small stone cottage – door half-open; window; trees in front; low wall to front.

John Nash is usually associated more with East Anglia than with the Cotswolds, and I have to say that this cottage – what one can actually see of it – does not quite look like a typical Gloucestershire cottage. For a start, it appears to be single-storey and built of very thin pieces of stone, some barely more than slivers, rather than the blocks of Cotswold stone one expects to see. The doorway is as plain as possible, while the tiny ‘six-over-six’ sash window seems quite out of scale and position. Odder still is the garden wall which is drawn as if it were made of hard-edged concrete. The entrance to the garden appears to be obstructed by a low hedge that seems to have insinuated itself between the gateless gateway and the front door. And although the neat flowering plant, bottom right, appears cheerful enough (contrast it with the angry ill-defined scourings, top left) the encroaching shrubs and bushes are decidedly menacing.

Both before and after the Great War, Nash used to make summer expeditions to Gloucestershire. His oil painting, ‘A Gloucestershire Landscape’, dates from 1914; the trees is full leaf and the newly harvested field, with its neat furrows and carefully stacked stooks of corn, suggest mid-summer, early August perhaps. The scene – a bird’s eye view of a landscape almost too green, too perfect – is bathed in a shaft of sunlight, but one very soon to be extinguished by the gathering storm clouds in the top right-hand corner of the picture. It is hard to resist attaching the date August 4th to the painting’s title: the day Britain could no longer avoid entering the war.

Nash had fought in the Artists Rifles in 1916 and 1917, experiencing the Battles of Passchendaele and Cambrai before becoming an official War Artist in 1918. If the date of ‘Gloucestershire Cottage’ is correct (The Tate dates its own, numbered, copy of the engraving as 1925), Nash was still coming to terms with his wartime experiences: a sense of unease, or worse, often underlies what at first glance may seem like unassuming landscapes or botanical drawings of this period. What is more, like his brother Paul, John was experimenting with Surrealism and with Post Impressionism. I suggest that these tensions can be seen not only in the contrasts between the cottage and its surrounding foliage but also in the contrasting ways the roof and the stonework of the ‘Gloucestershire Cottage’ are engraved.

For Nash, printmaking involved techniques of craftsmanship that he found every bit as rewarding as painting in oils or watercolour. In 1920 he became one of the founding members of the Society of Wood Engravers, along with other artists such as Eric Gill, Gwen Raverat and Lucien Pissarro. That’s distinguished company to be in. In 1919 he had become the first art critic of the new and instantly successful journal of literature and the arts, The London Mercury. It would be easy, but a mistake, to dismiss ‘Gloucestershire Cottage’ as a work of little significance. Taken together with ‘A Gloucestershire Landscape’, it tells us a lot about the preoccupations of John Nash, an artist who is himself too easily dismissed, even today.

Adrian Barlow

To see more artworks from The Wilson collection go to the Art UK website (click here) or The Wilson’s website (click here).